Another American University (of the Caribbean) MD named to SG's office

Like Nesheiwat, Haridopolos is also a family doc who also misrepresented her credentials and also has few relevant qualifications

Earlier this year, Stephanie Haridopolos was named1 Acting Chief of Staff and Senior Advisor to the U.S. Surgeon General, which Axios Pro first reported last month. According to publicly available information, Haridopolos, a family physician, has no experience in the federal government, has no training or education in public health, and has no experience leading large organizations.

UPDATE May 14, 2025, 7:39 pm EDT: This article has been updated to include confirmation from Stetson University’s Office of the Registrar that the university has never offered an Associate’s Degree (Haridopolos claims on her verified LinkedIn profile that she earned one from Stetson in 1994), and that students may not earn two separate Bachelor of Science degrees—they may choose a minor, but the university only awards one B.S. (Haridopolos makes a completely different claim in official Florida records: that she earned a Bachelor of Science in Biology and a Bachelor of Science in Chemistry from Stetson in 1994.) And Albany Medical College confirmed that Haridopolos was unable to pass and obtain ECFMG certification—which U.S.-accredited residencies require of graduates of medical schools outside the U.S.—until nine months after graduating from the American university of the Caribbean School of Medicine, which is why there is a 15-month gap between when she graduated and when she began residency.

UPDATE May 15, 2025, 8:38 pm EDT: Haridopolos or her representatives made at least two separate updates to her verified LinkedIn profile since this article was first published, before either deleting it or temporarily taking it offline. See this article for more information.

But what Haridopolos does have is a lot in common with recently withdrawn surgeon general nominee Janette Nesheiwat. And not only in their biographical details, but in the ways they have misrepresented their education and credentials—sometimes in strikingly similar fashion.

Both grew up in Florida. Both studied at the same undergraduate institution. Both obtained their medical degrees outside of the United States (in fact, from the same business in the Caribbean). Both chose family medicine residencies. Both worked in primary care.

Both are board-certified in family medicine. Both are licensed to practice medicine in the State of Florida (the only state in which Haridopolos is licensed; Nesheiwat is also licensed in Arkansas, California, New York, and the District of Columbia).

Both are related to Members of Congress from Florida (although, unlike Nesheiwat’s brother-in-law, former Rep. Mike Waltz (FL-06), Haridopolos’s husband, Rep. Michael Haridopolos (FL-08), is currently in office).

Both were recently involved in “divestment” of private companies from which they and their close relatives did or do stand to profit: both do (or did) own businesses in Florida; Nesheiwat reported that she had divested of the supplement company she founded, in anticipation of confirmation; state records appear to show that Haridopolos has not.

Both have no reported education or training in public health, nor any apparent record of peer-reviewed publications as physicians.2

The two have other things in common, too: neither have been

completely forthcoming about their backgrounds.

The two have other things in common, too: neither have been completely forthcoming about their backgrounds. For instance, both have misrepresented key aspects of their undergraduate experience. Both have used variations of the name of that Caribbean business that omit the word “Caribbean.” Both have shifted attention away from that education by stating that they studied in London.

And both misrepresented their medical education on their verified LinkedIn profiles.3

And both have a record of promoting themselves in ways that appear to try to influence public perception of their credibility and expertise.

However, on Haridopolos’s verified LinkedIn profile, in the

“Education” section, she lists having earned two degrees there.

Undergraduate education

Haridopolos attended Stetson University (Nesheiwat began at the school, but transferred to the University of South Florida to complete her bachelor’s degree).

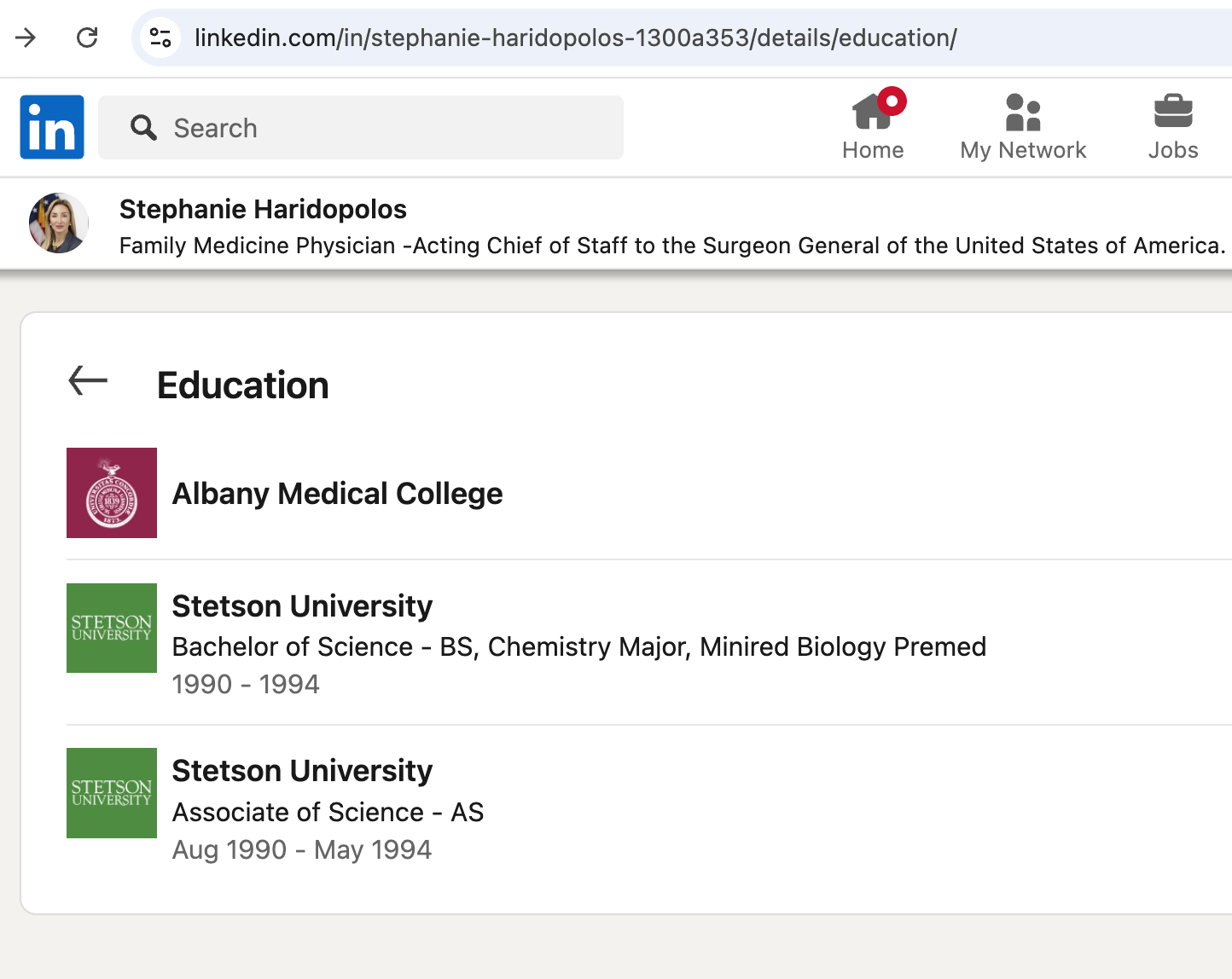

On Haridopolos’s verified LinkedIn profile, in the “Education” section, she lists having earned two degrees there: “Bachelor of Science - BS, Chemistry Major, Minired [sic] Biology Premed 1990 - 1994” and “Associate of Science - AS Aug 1990 - May 1994.”

However, Stetson’s 1994 commencement program shows that Stephanie E. Bressan (her birth name) earned one degree that year: a Bachelor of Science. A search of Stetson’s digital archives returned no evidence that Haridopolos earned any other degree from the school, then, or in any other year.

According to the Stetson University website,4 the school does not offer associate’s degrees, and does not appear to have done so when Haridopolos was a student there.

Given the manner in which this second degree is listed on her website—in its own row, with a specific degree name (both spelled out and abbreviated), it does not appear to have been a typographical error, such as “Minired” (for “Minored) in the row above.

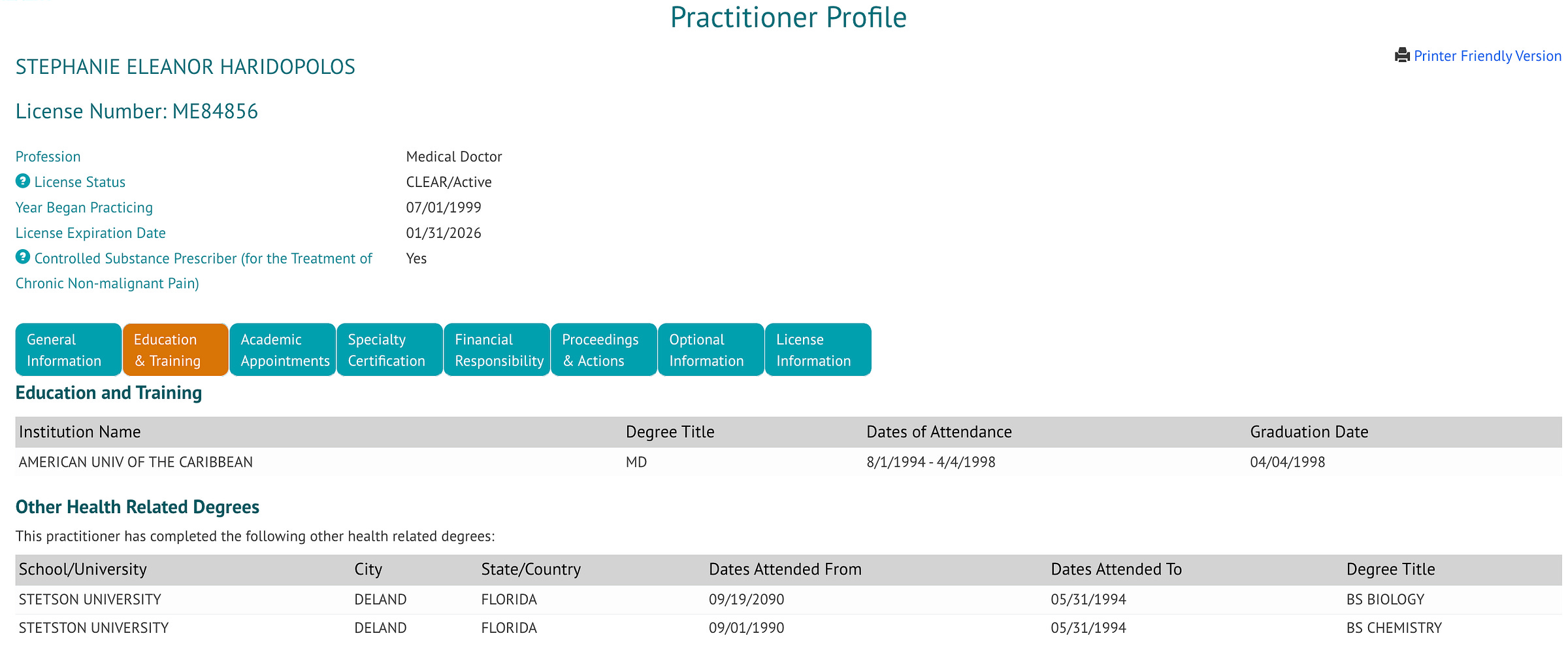

Perhaps more importantly, in Haridopolos’s self-reported physician profile—an official state record attached to her Florida license to practice medicine—she claims something different: rather than earning a BS and an AS, she asserted that she had earned two bachelor’s degrees from Stetson in 1994: a B.S. in chemistry and a B.S. in biology.

According to a review of Stetson’s website (a request for information to its media department was not returned) it appears not to have offered a dual degree in chemistry and biology at the time Haridopolos was a student there, nor since.

Stetson University's Office of the Registrar confirmed that it has never awarded an Associate’s Degree, and that students may not earn (and could not do so while Haridolpolos was a student there) two separate Bacher of Science degrees at the same time; they may choose a minor, but the university awards only one B.S. These facts directly contradict Haridopolos’s claims on her LinkedIn profile and in official Florida records of, on the former, having earned an A.S. in Science from Stetston in 1994, and, in the latter, having earned a B.S. in Biology and a B.S. in Chemistry, also in 1994.

Medical education

According to multiple public records, Haridopolos graduated from the American University of the Caribbean School of Medicine in 1998 (Nesheiwat graduated from the school in 2006). Haridopolos completed the program in four years; Nesheiwat took six (for as-yet unexplained reasons).

And Nesheiwat and Haridopolos did almost the same thing on their LinkedIn profiles, making it seem as if the academic institution affiliated with the residency they completed is the school where they earned their degree—when it is not.

… making it seem as if the academic institution affiliated with the residency

they completed is the school where they earned their degree—when it is not.

However, Haridopolos does not include the American University of the Caribbean (nor any variation of that name) on her LinkedIn profile.

Instead, she lists the school affiliated with her residency program, Albany Medical College. But—unique among the three educational institutions listed—she does not include any degree. Nor does she indicate anywhere on her profile that she completed a residency at Albany Medical Center, now known as the Albany MED Health System.

Nesheiwat was more bold, claiming directly that she obtained her “Doctor of Medicine - MD, Medicine” from a university at which she had never been a student.

Haridopolos is slightly more circumspect, not explicitly stating that she obtained her M.D. from Albany Medical College. But—in the absence of the true fact of her M.D., and that Albany Medical Center was where she completed her residency, not attended medical school—readers of her profile may be left with the false impression she earned her degree from that college.

However, like those who complete residencies affiliated with the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Albany residents are not students, and they do not “graduate”—they complete the program.

And in her Florida medical license physician profile, Haridopolos does not list “Albany Medical College” for her residency; rather, she lists “Albany Medical Center.”

In addition, in some articles, Haridopolos is described as having attended the “A.U.C. School of Medicine.”

In addition, she claims to have completed her residency only 18 months later.

Residency

In that official profile, Haridopolos’s dates do not add up. Family medicine residencies take three years to complete, and typically begin within a few months of completing medical school. But she claims to have begun her residency 15 months after graduating, without explaining that large gap. In addition, she claims to have completed her residency only 18 months later.

While there is an obvious typographical error in the last date ("0001”—which is most likely "2001"), even if she had begun residency immediately after graduating, she still would not have completed it in the timeframe she included in that official record.

In the Florida profile, she lists 1999 as the year she began practicing, not 1998, the year she graduated from medical school. But in the “About” section of her LinkedIn profile, she writes, “I have been in medical practice since 2002 after completing my residency program at Albany Medical Center in the same year.”

If Haridopolos failed to match in 1998, and so had to find an alternate pathway to residency, she may have completed an internship and then re-applied for a residency. This would explain why she, in one instance, claims to have begun practicing in 1999. It would not, however, explain how she completed a residency in 18 months.

Nor would it explain why she did not report this possible alternate pathway, if she availed herself of it, in her official state records.

Albany Medical College confirmed that Haridopolos was unable to pass and obtain ECFMG certification—which U.S.-accredited residencies require of graduates of medical schools outside the U.S.—until nine months after graduating from the American University of the Caribbean School of Medicine, which is why there is a 15 -month gap between when she obtained her M.D. and when she began residency. ECFMG evaluates international medical graduates such as Haridopolos, making sure they meet the United States Medical Licensing Examination standards. The college also confirmed that Haridopolos completed her residency from July 1999 through June 2002 (which is not what her official state records reflect).

Making misleading, untrue, deceptive, or fraudulent representations on

a physician’s profile is expressly prohibited by Florida statute.

Board certification

According to her official Florida license profile, Haridopolos is board-certified in family medicine by the American Association of Physician Specialists. Its affiliated certification body is now the American Board of Physician Specialties, which offers the public the opportunity to verify a physician’s board certification.

However, a search of that database provides no results for Stephanie Haridopolos or Stephanie Bressan. It appears that Haridopolos may not hold the board certification she claims in official Florida records.

A search of the American Board of Family Medicine, another certifying body not affiliated with either AAPS or ABPS (but with the American Board of Medical Specialties), does produce a record for Stephanie Haridopolos. That record shows she was first certified on July 12, 2002—more than 18 months after she completed her residency, according to her official Florida profile. The website Certification Matters also confirms her ABFM certification, which she first obtained in 2002.

It is unclear why there is another gap between completing the residency and being first board-certified.

That ABFM record also shows that Haridopolos is currently “clinically inactive.”

The reasons for so many discrepancies between those Florida records and others publicly available are not apparent. That Haridopolos tells different stories about her undergraduate degree, medical degree, residency, and board certification—not just in traditional and social media, but in official state records—is concerning. Moreover, making misleading, untrue, deceptive, or fraudulent representations on a physician’s profile is expressly prohibited by Florida statute. Any person found guilty of such representations may face one or more penalties, including suspension or permanent revocation of their license.

Other positions

Haridopolos previously served as president of the Brevard County Medical Society. And she was named to Florida’s Board of Medicine. Members of that board—one of whom must be a graduate of a “foreign medical school”—meet bimonthly, and handle “disciplinary cases, licensure approvals, correspondence items, committee reports, policy discussion items and other necessary Board actions.” This falls under healthcare, not public health.

According to a 2024 profile on the website of the University of South Florida, she “has held positions with the Florida Coalition Against Domestic Violence Foundation, the American Cancer Society Making Strides Against Breast Cancer Walk and Attorney General Pam Bondi’s Florida Statewide Drug Task Force.” These, too, do not fall under public health.

From 2018 through her appointment to the surgeon general’s office earlier this year, Haridopolos served in the voluntary position of chair of the board of Florida Healthy Kids Corporation, a state-created non-profit. Then-Florida Chief Financial Officer Jimmy Patronis appointed her.5 IRS form 990 filings show that the role was uncompensated, and that she spent three hours a week in the position, on average.

The chair does not lead the organization (its CEO and other C-suite executives do), and from public reports, the post appears honorary and philanthropic.

Public health

In a recent interview with the University of South Florida, Haridopolos said—about her appointment to the Office of the Surgeon General—“In my new position, I’ll continue my work with public health, but on the federal level.”

What she meant by that is unclear. There is no public record of Haridopolos training or working in public health. In interviews over the years, she has mentioned sometimes lobbying for legislative changes in Florida, including for bills related to health care. Volunteering with charities, medical societies, and boards, serving on the board of a publicly funded health insurance nonprofit, and advocating for change is admirable. But they are not parts of a broad definition of, and do not signal nor confer expertise in, public health.

“In my new position, I’ll continue my work with

public health, but on the federal level.”

The one achievement related to public health most often cited about Haridopolos is an award she received in 2024.

Since 1988, the University of South Florida College of Public health has annually6 honored “women in Florida who made significant contributions to the field of public health” by bestowing upon them the Florida Outstanding Woman in Public Health award.

According to the college’s website,

The first recipient of the award was Dr. Flora Mae Wellings, retired director of the State Epidemiology Research Center. She served as director for 18 years and was instrumental in finding solutions to many of Florida’s environmental public health problems. Nominees should be someone whose work significantly contributed to the field of public health in Florida. Candidates may represent any sector of public health, including maternal/child health; health policy, management, finance or economics; epidemiology and biostatistics; environmental and occupational health; public health nutrition; public health nursing; international health; health education; and, toxicology/parasitology.

At least ten award recipients had earned the degree of Master of Public Health. Many had served as administrators of county health departments or in the Florida Department of Health. And most had served full-time in public health positions for 20 years or more prior to receiving the award.

In addition to offering health insurance plans, Florida Healthy Kids, the nonprofit of whose board Haridopolos was chair, has offered eight small grants to partner organizations to expand access to those plans. In recent years, they have amounted to between $48,000 to $52,000 in total. Other than these grants (or those like it)—directly connected to the work of the organization—it does not appear that it awards gifts.

Except, in October 2023, when Haridopolos, as board chair, presented the University of South Florida College of Public Health with a gift of $100,000 from Florida Healthy Kids to establish an endowment fund in memory of the college’s founder, Samuel P. Bell III.

That single gift is as much as double the total amount of grants Florida Healthy Kids awards annually to increase access to the plans it offers, and appears to be the first of its kind from the organization.

Six months after Haridopolos made that gift to the college, it awarded her the 2024 Florida Outstanding Woman in Public Health, for advancing “meaningful outcomes toward the mission of providing comprehensive, affordable, quality healthcare for Florida’s children.”

Three weeks later, Haridopolos’s husband declared his candidacy for Congress. And a few weeks after he took office, Haridopolos was named Acting Chief of Staff and Senior Advisor to the U.S. Surgeon General.

Chief of Staff

The Surgeon General provides operational command of the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) Commissioned Corps, one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. The Chief of Staff of this office has largely been a career position, mostly not for political appointees. This is precisely because, more than in many agencies, the job is not simply management of the office, and requires leadership of many crucial and technical aspects of the USPHS.

A brief review of two of the officers who have served as chief of staff in the recent past illustrates both its significant responsibilities and substantial required qualifications.

Retired U.S. Public Health Service Rear Admiral Robert C. Williams, P.E., M.Eng., D.AAEES, F.ASCE, was formerly the Chief of Staff in the Office of the U.S. Surgeon General, acting Deputy Surgeon General, and Assistant Surgeon General. Prior to that, Admiral Williams served as director of the Division of Health Assessment and Consultation of the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, and as the Public Health Service’s Chief Engineer. He earned a B.S. in Civil Engineering and an M.E. in Environmental Engineering, with postgraduate public health education.

As Chief of Staff, according to an official biography, he provided

direction and oversight to five offices (Commissioned Corps Operations, Force Readiness and Deployment, Reserve Affairs, Military Liaison and Veteran Affairs, and Science and Communications). In this capacity, he serve[d] as the Chief Operations Officer to the 6,000-plus members of the USPHS Commissioned Corps. He [wa]s also an integral leader in the ongoing Transformation of the Commissioned Corps.

Retired U.S. Public Health Service Captain Joel D. Dulaigh, MSN, ACNP-BC, FAANP, was also recently the Chief of Staff, and Senior Program Officer, in the Office of the U.S. Surgeon General, and USPHS liaison to the American Association of Nurse Practitioners.

He earned a B.S. in Nursing Education and an M.S. in Nursing, and served as a nurse in the U.S. Navy and Naval Reserve for 14 years (with prior service in the Army National Guard), including 10 years of active-duty naval service, in the White House Medical Unit and in other Navy healthcare facilities. He then served as a Nurse Practitioner in the USPHS Commissioned Corps for more than nine years, including as the Director of Diving Medicine in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, before becoming Chief of Staff.

Others who have held the position have had extensive experience in both federal public health leadership and administration.

Business interests

From 2004 through 2024, Haridopolos’s husband, now-U.S. Representative Michael Haridopolos, owned and operated a lobbying and consulting firm, MJH Consulting. He was a registered lobbyist in the Florida legislative branch from at least 2015 through 2024 (and in the executive branch from 2013) at the same address as that firm is registered with the state of Florida. Several of his clients were healthcare organizations, including at least one health insurance company.

Sometime after he was elected to Congress last year, he apparently divested of the firm; in the most recent annual report filed with state of Florida, he is no longer listed, as he had been for many years, as its “PSTD” (President, Secretary, Treasurer, Director).

The lobbying firm’s annual report, signed January 2, 2025, now lists Stephanie Haridopolos in the position of PSTD. As of this writing, the firm remains active. There have been no changes since then to its articles of incorporation (transferring it to anyone else, for example), nor any amended filing updating ownership, nor any dissolution filed. While she does not appear in a search of registered Florida lobbyists for 2025, absent additional information, it appears that she remains in control of the lobbying firm while also serving concurrently in a high federal position.

In the recent USF interview, Haridopolos offered her view of her new role:

“Getting involved in statewide health policy has driven me to help more people,’’ she said. “When the opportunity arose with this administration, I felt that the stars were aligned for me to take all this experience I had on the front lines and funnel it into a federal position. That’s why I’m here.’’

It is unclear who made the appointment, and under what authority.

Under her birth name, Stephanie Bressan, she co-authored an article with a chemistry professor and another author that was published, after she graduated from Stetson, in the Journal of Chemical Education; she developed part of the work as part of her Senior Project in chemistry.

Haridopolos’s addition to her LinkedIn profile of her new workplace, HHS, was verified using work email less than three months prior to the publication of this article.

Including a review of the earliest versions of the site available on the Internet Archive, which date to two years after Haridopolos graduated.

Professionals should list their credentials clearly and without obfuscation. Misleading the public, even by omission, is wrong.

I’ve known many fine physicians who graduated from her medical school. She should be proud of her Alma Mater, rather hide it.