Janette Nesheiwat’s Shifting Stories About Her Disaster-Relief Experience

Trump's surgeon general nominee's public accounts of her disaster-relief work conflict with earlier statements, public records, and known facts

President-elect Donald Trump announced on November 22, 2024, his intent to nominate urgent-care physician Dr. Janette Nesheiwat to the position of surgeon general of the United States. In addition to troubling instances of Nesheiwat repeatedly making claims and statements about her professional qualifications for the job that have been demonstrably false, she has seemed to try to enhance her apparent capability to perform the leadership aspects of the role. This article is the first to detail and examine those attempts.

Until April 20, 2024, what little press attention the nominee had garnered recounted an early family tragedy or, to a much larger extent, simply credulously repeated the qualifications she and others have repeatedly claimed, over at least the last 15 years, that she had earned, without verifying them.

On that day, I broke the news on this Substack that Nesheiwat misrepresented, selectively omitted, and/or lied about her medical education, board certifications, and military experience, and examined those statements in detail against the public record and other known facts.

In that article, I detailed some of the steps Nesheiwat has taken to apparently seem as if she is more qualified than she is. Nesheiwat lacks the statutory requirements of the position, as well as most of the other qualifications—other than a medical degree, license to practice medicine, and widely recognized board certification—that other modern surgeons general have earned.

But Nesheiwat is a single-specialty doctor who was not able to commission as a military officer; obtained her medical degree outside of the U.S.; became a walk-in-care provider who also sells a health supplement and was for a few years an on-air contributor to Fox News; has apparently not published in any medical or other scientific journals; and has no apparent credentials in public health.

I also showed how, in addition to augmenting her qualifications with details that are not factually true, she has attempted to change potential negatives into positives.

For example, rather than admit she was medically disenrolled from the Reserve Officers Training Corps prior to commissioning, she would say that she had simply chosen—even after (she claimed) having completed “Advanced Officer Training”—to not pursue a career in the Army.1

Rather than admit that she had to seek her medical degree from a school outside the United States (and took 50% longer to complete it than the average US medical student), she would instead have begun her studies at “the American University” and “completed the majority of her studies in London.”

Rather than lean into the fact that she is a single-specialty doctor at an urgent-care chain, she would be a highly credentialed prolific hero who was “saving lives in the ER” as a “double-board certified” “emergency medicine physician.”

And rather than report that she was a paid talking head on partisan infotainment shows, she would advertise herself as a “prominent voice” seeing the nation through two major health crises: as a “White House Advisor & Spokesperson on the Opioid Crisis,” and while working “on the front lines in New York City” during the COVID-19 pandemic.

But it is, perhaps, in discussing her responses to the medical needs of victims of natural disasters that Nesheiwat has been the most insistent that she has demonstrated the experience and leadership qualities necessary to accept the mantle of responsibility that has been her dream.

A kid who grew up in a small town in Florida, got her degree in the Caribbean, and completed a family practice residency in Northwest Arkansas who now treats earaches, hives, UTIs, stomach flus, allergies, and cuts, scrapes, sprains, and breaks—and serves as one of the medical directors at a for-profit regional healthcare company—does not necessarily get to become surgeon general of the U.S.; she would also have had to have “led disaster-relief missions around the globe with the American Red Cross“ and other charities.

Disaster-relief missions

The organization UkraineFriends.org announced on October 19, 2022 on its Instagram account that Nesheiwat would be a guest speaker for its “Special Evening to Support Ukraine.” It wrote, “Whether she’s treating patients in the emergency room, serving with the American Red Cross as a disaster relief doctor, or sharing critical information with TV audiences, Dr. Janette is a top Family and Emergency Medicine doctor.”

In its March 16, 2020, announcement adding Nesheiwat as a medical correspondent, Fox News said that she “has led medical relief missions around the globe with the American Red Cross.”

The “About” page on Nesheiwat’s personal website now states, “She has led medical relief missions around the globe from Haiti to Ukraine to Africa.” Until two months before Trump announced her as his choice for surgeon general, that page said she served “on the front lines of disaster relief with the Red Cross.”

A 2022 interview with Nashville Voyager magazine also said that Nesheiwat served “on the front lines of disaster relief with the Red Cross.” She went on to say that she had recently returned from Ukraine, “where I led a medical mission caring for hundreds of Ukrainian refugees in need…”

When initially contacted, the American Red Cross said that it could not immediately confirm or deny whether Nesheiwat had ever led any missions for the organization, but a spokesperson for the organization promised to search its relevant records—some of which, they said, are older, and therefore not electronic, and that it might take some time to complete. Soon after, however, the American Red Cross stopped responding to all inquiries.

Nesheiwat did travel to Haiti in 2010, though, a little more than a year after completing her family medicine residency.

However, there is no public evidence that Nesheiwat led this effort.

According to a contemporaneous article in the Palm Beach Post about her brother-in-law, the singer Scott Stapp, the trip was in conjunction with his and his wife Jaclyn’s (Nesheiwat’s sister) now-dissolved charity, the With Arms Wide Open Foundation, and a group from a church in Boca Raton.

Another report at the time stated that the singer and other musicians were supporting the relief efforts of DC3 Music Group LLC:

an MD-80 aircraft is scheduled to depart for Haiti from Long Beach, Calif. on Wednesday. The aircraft will transport doctors, medical staff and 10,000 pounds of medical supplies to the hard-hit Haitian capital, Port-Au-Prince. Waiting on the ground will be Creed’s Scott Stapp (pictured). Be nice — he’s taking an admirable hands-on approach with this one. Others, such as New Kids on the Block, helped by soliciting donations from fans while leading by example.

Nesheiwat reportedly accompanied the church group from Florida, not the DC3 group from California, arriving about two weeks after the earthquake. The Post article quotes Stapp upon returning a week later as saying, “All the hard-core trauma needs have been taken care of. Now it’s all about preventing the spread of disease, food, water sanitation, clothing, shoes.”

And despite her later claim that she led the mission for the American Red Cross, an earlier version of her personal website said:

Perhaps the 36-year-old physician’s most life-altering example of ‘being there in immediate need’ happened when she headed a medical relief mission following the devastating Haiti earthquake in 2010, along with her brother and brother-in-law in coordination with the With Arms Wide Open Foundation and members of Spanish River Church.

Changing stories

In her book, Beyond the Stethoscope: Miracles in Medicine, published in December 2024, about a month after her nomination, Nesheiwat tells a story that’s very different from her claim about the American Red Cross, and different from the stories she had told earlier, and which the Palm Beach Post had recounted.

She now claims, in the book, that she volunteered in Haiti in 2020 while she was still a resident at a program associated with the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, and that she personally created it, cobbling together the mission out of donations, contributions of supplies from the residency hospital, and “rallying” two members of her family (but not, apparently, Stapp) and two colleagues to join her.

Nesheiwat writes that she was motivated to help after the “horrible earthquake… It was a 7.0—exceptionally severe—whose center was at a town about fifteen miles southwest of the capital city Port-au-Prince.”

While she does not provide an explicit date, she is describing what must be the 2010 disaster. But that account of her involvement—what she was doing when the earthquake struck, what her job was at the time, and the circumstances of her trip—does not align with known facts, nor with her earlier recountings.

She claims to have been a medical resident at the time, “making $30,000 a year.” However, records show she had completed her residency in 2009, more than a year before the earthquake in Haiti.

She claims that at the time of the earthquake, she had just completed an “extended shift at the hospital” in Arkansas where she worked. But on her personal website, her earlier bio claimed that she had cut short a “family vacation” to go on that relief trip to Haiti.

She recounts in the book that she immediately “jumped into high gear… Gathering up medical supplies from the hospitals I was connected with, pooling donations, and rallying my brother Danny and nephew Jon Paul, along with a pharmacist and a nurse who willingly jumped on board, became my mission.”

She continues,

My local hospital where I worked donated lots of supplies for me to take with me… I recall in the line at the airport, they wanted to charge me for all the supplies I was bringing with me. Everyone in the line started opening their wallets to help me pay for all the supplies to be shipped to Haiti, until the manager of the airline came out and waived all the hundreds, as it was for a good cause, humanity.

The Palm Beach Post article reported that Stapp “is one of several musicians in the DC3 Music Group charity organization that helped pay for and load a plane full of supplies for earthquake victims.” And the article states that Stapp and the Nesheiwats joined the group from Spanish River Church in Boca Raton in order to travel to Haiti.

Near the end of her account in the book, Nesheiwat writes, “I called my boss, Dr. Turner, back home in Fayetteville, telling him I wouldn’t make my ER shift that weekend. Haiti he held me tight. He understood and told me to be safe.” However, the Post article says that it was a weeklong trip, one that apparently had been planned to be for that length of time. She might have been referring to Dr. Sammy Turner, a physician at Washington Regional Medical Center in Fayetteville; Dr. Turner did not immediately return a call for comment.

Nesheiwat also includes something noteworthy, a detail that seems odd to have not made it into the Post article: “In an unexpected twist, an NFL team owner sent his private jet to pick us up after weeks of work and then being stranded. It was not easy to exit Haiti. Funny how help shows up in surprising forms.”

Other disasters

In a different part of her book, Nesheiwat writes, “I was well acquainted with the trauma and desperation that lingered from treating hundreds of injured patients from Hurricane Katrina in 2005…” She says she volunteered in Chicago, in “large indoor areas such as gymnasiums,” where she says the Federal Emergency Management Agency had brought hundreds of victims by bus.

According to public records, Nesheiwat was a student at the American University of the Caribbean (AUC), in Sint Maarten, from 2000 to 2006. In August 2005, when Katrina made landfall in the United States, Nesheiwat was beginning her fourth year at AUC—but, as she has separately claimed, she was completing her medical studies in London, England.

According to Standard 9 of the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, medical students may not treat patients unless “appropriately supervised at all times in order to ensure patient and student safety.”

And it is unlikely (although not impossible) that medical school administrators would grant a fourth-year student leave from their carefully planned and scheduled clinical rotations to assist in a disaster-relief mission, much less one so far away.

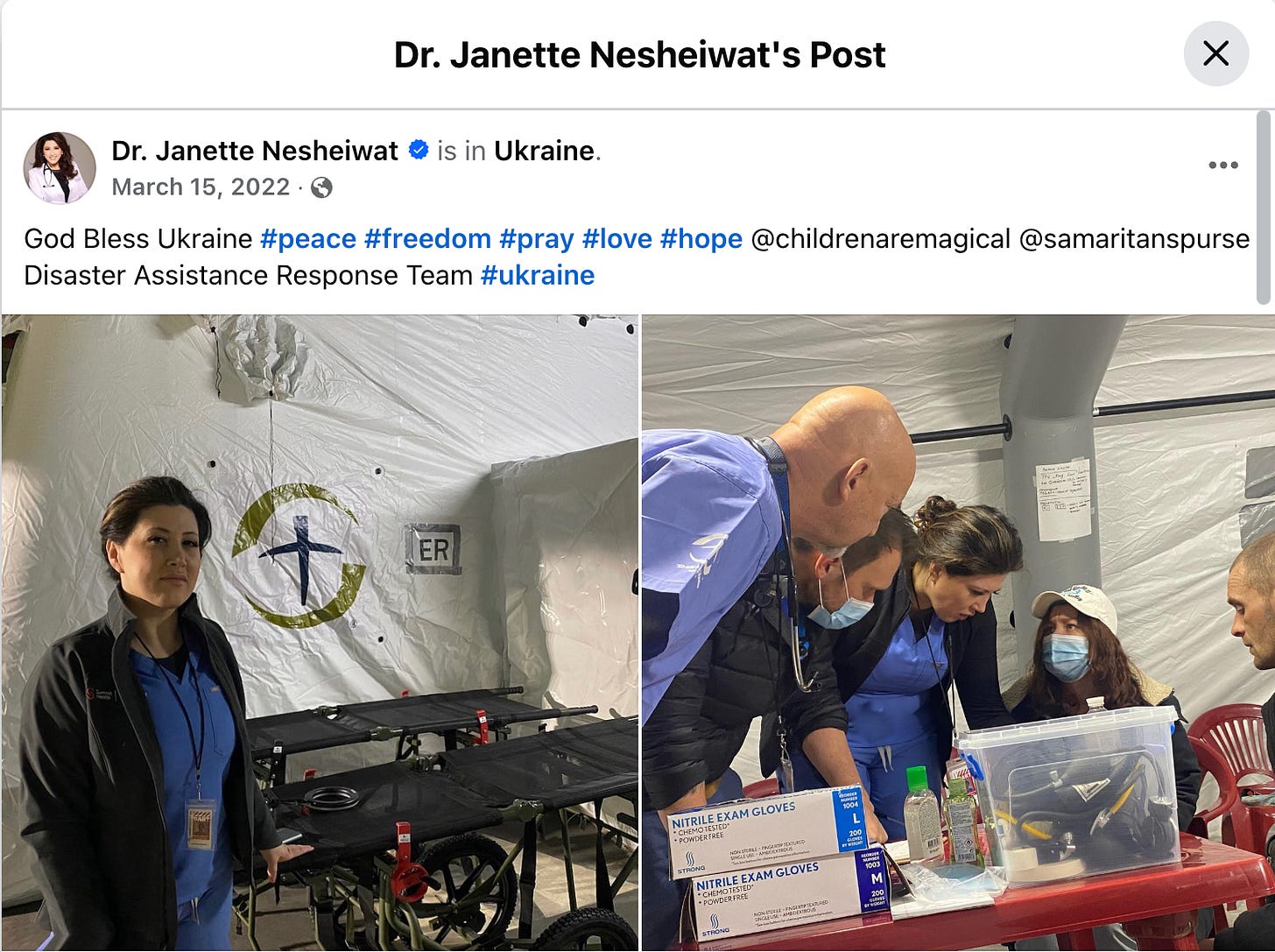

In numerous social media posts and interviews over several years, and on her personal website, Nesheiwat has described at least one of the missions she has led as having been sponsored by the Children Are Magical Foundation, or CHARM. And she has, simultaneously and in other forums, stated that she is a member of Samaritan’s Purse Disaster Assistance Response Team, or DART.

What she rarely includes in her stories about CHARM is that her sister, Jaclyn founded the charity.

In fact, in a way, so did Nesheiwat.

In CHARM’s original articles of incorporation, dated June 2, 2011, and filed in the State of Florida, Janette Nesheiwat is listed as the vice-president of the foundation and a member of the board of directors—along with her mother, Hayat Nesheiwat; her sisters Julia Nesheiwat and Dina Nesheiwat; her nephews Jon Paul Nesheiwat and Jagger Stapp; and another individual whose relationship to the family is not readily apparent.

The Stapps, who according to public records live in Tennessee, appear to run the foundation from that state, even though it is still registered in Florida.

A search of Tennessee’s charity records produced no financial statements available for CHARM, although the state does exempt some charities that take in less than $50,000 annually from filing. However, in addition to being able to access the filings of non-exempt charities, Tennessee says that it offers public searches for exempt charities, too, which must annual file an exemption request.

Neither CHARM, nor “Children Are Magical,” appear in either search.

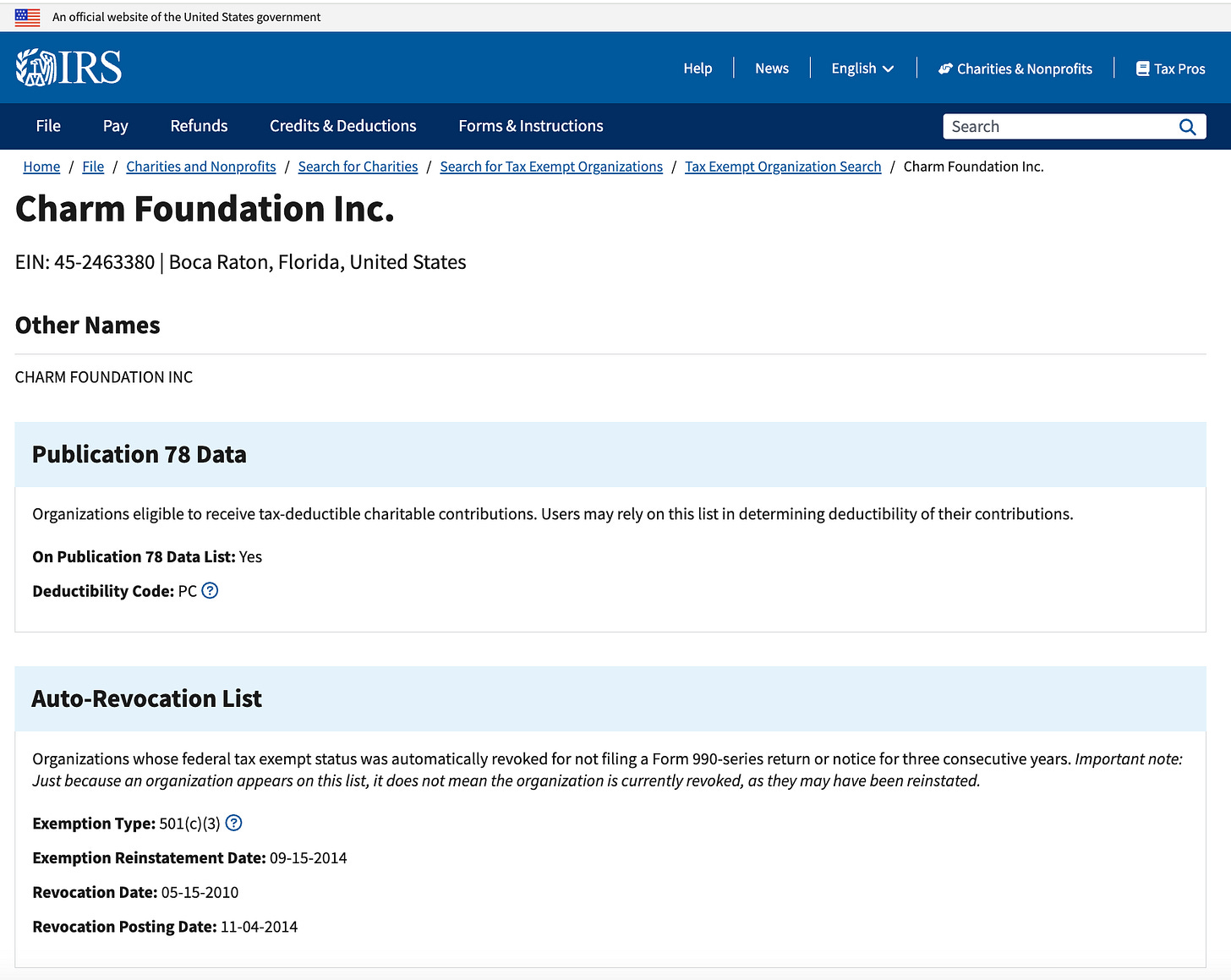

CHARM does file basic annual reports in Florida—which do not include financial information—where it is also registered with the federal Internal Revenue Service as a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization.

For tax years 2014 (when the IRS approved its request for reinstatement, after apparently not having filed required documents for three consecutive years) through 2024, CHARM submitted the brief federal 990-N “postcard” form, which charities may file if they normally have receipts of less than $50,000.

In dozens of posts on its Facebook page over several years, CHARM showcases the work it does in Tennessee for low-income families, such as back-to-school drives. A review of the posts reveals that the only apparent mention of international medical missions are those that feature Nesheiwat.

And it is unclear how CHARM—whose stated mission is “to heighten awareness of children’s issues and provide underprivileged youth with the tools for enriching their lives through education, encouragement, and valuable resources”—could have sponsored a disaster-relief missions to another country that treated “hundreds” while appearing to take in less than $50,000 a year (while providing other services in Tennessee, too). Particularly in Ukraine, where, Nesheiwat has claimed, the mission she says she led cared for “hundreds of Ukrainian refugees in need.”

Samaritan’s Purse did not answer emailed questions about whether Nesheiwat ever led any of its disaster assistance teams, nor if it was possible for someone whom one charity had sponsored in traveling to another country for a relief mission to then lead a Samaritan’s Purse Disaster Assistance Relief Team instead.

But in replies, a spokesperson for Samaritan’s Purse did write, “We can confirm that Dr. Janette Nesheiwat has served with Samaritan’s Purse as part of our Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART)” and that “served with us in Ukraine in 2022.”

And they wrote that only its full-time employees—and not those contracted members who are “vetted, interviewed, and hired to be on a roster for us to call upon them when a disaster strikes” when it deploys DARTs on missions—lead them. Such team members are compensated, not unpaid volunteers.

Among the current requirements for physicians who wish to apply for a contracted position on a Samaritan’s Purse DART team are relevant clinical experience in a specific field of practice within the last five years; completion of accredited training as a physician specializing in relevant specialty; and maintaining a personal relationship with Jesus Christ and being a consistent witness for Jesus Christ.

Photographs from her Facebook page that Nesheiwat noted as having been from this mission—one she claims to have led—include Samaritan’s Purse logos, and she can be seen wearing a Samaritan’s Purse DART identification badge.

A search of the Samaritan’s Purse website for “DART” yielded dozens of results, including detailed stories of the work its teams have performed around the world, some including the names of those who led them, and others who have donated their time to help. Many of the stories mention Ukraine.

A search of the Samaritan’s Purse website for “Nesheiwat,” however, yielded no results.

The Last Campaign is a reader-supported publication from an independent, freelance writer. To receive new posts and support this work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Throughout this article, all quotations from and descriptions of information found online are current as of the time of publication, except where otherwise noted and/or linked to archived versions.